Defunding Planned Parenthood could mean struggles for health centers

Published by the Scripps Howard Foundation Wire on Nov. 25, 2015

By Rebecca Anzel and Jessica Pereda

Reporters — Fall 2015

WASHINGTON — Scott County, Ind., is a 190 square mile, rural area on the southeastern edge of the state. Thirty-six miles north of Louisville, Ky., it is home to about 24,000 residents.

As with countless Midwest towns, the county has wide open spaces. Weekends, the local concert hall draws crowds with live music. Scott County also has a low college-education rate and high drug use.

One thing the county is short on is medical care — there are 25 practicing physicians, a ratio of one doctor for every 960 patients. That’s below the 2011 national rate of 2.5 doctors per thousand people, according to the World Bank. It was also ranked the most unhealthy county in Indiana five years in a row.

The Planned Parenthood Clinic in Scottsburg, the county seat, closed in 2013 because it lost state funding. And there have been consequences.

From 2004 to 2013, the county had five reported cases of HIV. In 2015, that number jumped 3,520 percent to 181 cases. The only difference, according to some officials, is the number of medical providers.

The state has a complicated history with Planned Parenthood. Indiana became one of the first states to try to exclude Planned Parenthood from the Medicaid program in 2011, an effort eventually overturned by the courts. That was followed by numerous other efforts to restrict funding to the public health system.

Scott County’s clinic is one of five that has closed since 2011 as a result. It left an area struggling from what the state health department called an “opioid epidemic” with no HIV testing facilities, although any physician can perform the test.

“I think the HIV outbreak has a host of environmental issues, but yes, the clinic that was in Scottsburg was one of the only HIV testing centers,” Kristin Adams, president and CEO of the Indiana Family Health Council, said. “That doesn’t mean docs weren’t testing, but the fact is, did we miss an opportunity? The possibility is there.” IFHC manages public family planning funds.

While loss of the Planned Parenthood clinic was not a direct cause of the HIV outbreak, its services increased education, awareness and testing for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. Since the outbreak, the Indiana State Health Department began a needle exchange program and introduced a mobile health clinic that does testing.

A national problem

A Herculean struggle between pro- and anti-abortion groups reignited in July after videos were released showing Planned Parenthood officials speaking about how the organization supplies fetal tissue to be used in research. Planned Parenthood President Cecile Richards was called as a witness in a House Oversight and Government Reform Committee hearing in September.

Critics of Planned Parenthood have called for Congress to withdraw the group’s public funding for a year while an investigation is conducted. Several states have initiated investigations into Planned Parenthood.

Politicians who are calling for Planned Parenthood to be defunded have said the solution to end the gap of care, should Planned Parenthood lose federal funding, would be to redirect funds to federally qualified health centers, community health centers that offer comparable services.

“I support legislation that would strip roughly $540 million in federal funding away from the Planned Parenthood Federation of America or any of its affiliate organizations and redirect it to women’s health care services at facilities like community health centers,” Sen. Dan Coats, R-Ind., said in a statement.

Others have said it might not be that simple.

“Community health centers really are not equipped and should not be expected to be equipped to fill the gap in the safety net that would be left if Planned Parenthood were defunded,” Kinsey Hasstedt, public policy associate at the Guttmacher Institute, said.

Sara Rosenbaum, founding chair of the Department of Health Policy at the George Washington University School of Public Health and Health Services, echoed that thought in a piece she wrote for Health Affairs.

“A claim that community health centers readily can absorb the loss of Planned Parenthood clinics amounts to a gross misrepresentation of what even the best community health centers in the country would be able to do were Planned Parenthood to lose over 40 percent of its operating revenues overnight as the result of a ban on federal funding,”she said.

Community health centers saw 22 million patients nationally in 2013. According to the National Association for Community Health Centers, the cost per patient visit was $644 in 2012. Federal funding covered $344 of that. While health centers could have additional sources of funding — including loans and other grants — many still struggled to close that gap.

Planned Parenthood is different in that “other health-care providers do not raise private dollars to ensure that their patients can get the care that they need if they are unable to pay themselves, and we do,” Betty Cockrum, president and CEO of Planned Parenthood of Indiana and Kentucky, said.

While loss of federal funding would not automatically result in the closure of all 652 Planned Parenthood clinics across the U.S., 5 percent to 25 percent of the organization’s patients would be at risk of losing health care, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

Planned Parenthood clinics saw 2.8 million patients across the country in 2014, according to its website. A 2014 Guttmacher Institute report found that, although Planned Parenthood clinics represented 10 percent of all health centers, the health-care provider served 36 percent of family planning clients.

With additional patients looking for medical services, stress on health centers would intensify.

Sending additional funding to these health centers would be of tremendous help, but some officials say that effort might not be enough to avoid a public health-care problem.

Rosenbaum said it will be hard for community health centers to immediately use money previously allocated to Planned Parenthood because “there’s a gulf between that assertion and being able to provide that care.”

How public health-care funding works

Planned Parenthood and community health centers receive Medicaidreimbursements and family planning grants under Title X of the Public Health Service Act. The two, with other smaller grants, make up about 40 percent of Planned Parenthood’s revenue.

Medicaid is a federal-state partnership that pays for health care for people with low incomes. State governments decide which programs or services they want to fund, and in some cases they can choose how much money to allocate to health clinics.

Medicaid also pays for care in hospitals, nursing homes and doctors’ offices.

The federal government spent $330 billion on Medicaid in fiscal 2015, according to the Office of Management and Budget.

Title X, the only federal grant program dedicated to family planning, started during the Ronald Reagan administration. Grants are awarded to a variety of agencies, including hospitals and independent health centers. The law dictates that recipients of the grants must follow specific rules and regulations.

But money under Title X hasn’t kept up with inflation. The Guttmacher Institute found the Title X grant program would need to receive $941.5 million to keep up with the price of medical care. In 2014, Congress allocated $286.5 million.

“The need is going up – the financial support for this program is going down because Congress is cutting it,” Hasstedt said.

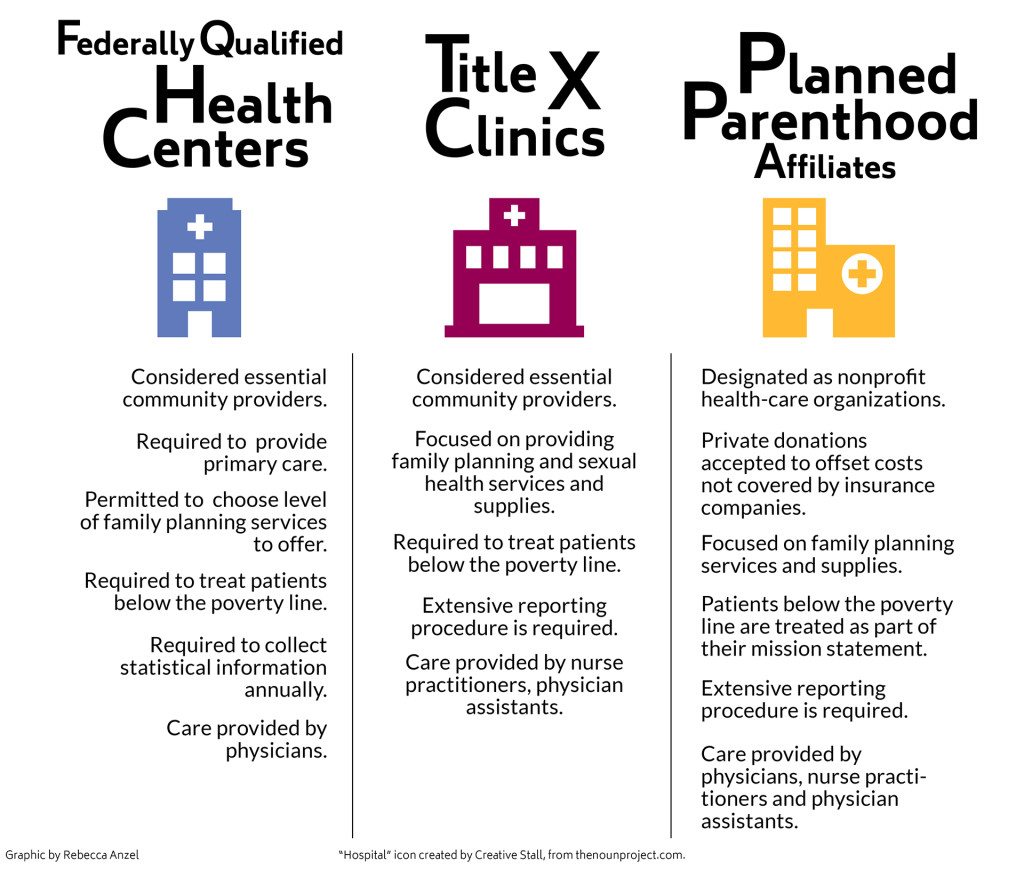

Federally Qualified Health Centers and Planned Parenthood affiliates can receive Title X grants if they apply and meet the criteria. If they receive these grants, the middle section of the graphic is applicable. SHFWire graphic by Rebecca Anzel.

According to the Guttmacher Institute, “Medicaid pays for core clinical care, while Title X and other grant programs buttress the system of family planning centers and fill gaps in services and coverage.”

Abortions cannot be funded through Title X grants. Medicaid pays for abortions only in cases of rape, incest and danger to the mother’s health.

Planned Parenthood received $528 million in 2014 through Medicaid and Title X. Community health centers were allocated $11 billion over five years, beginning in in 2014.

Planned Parenthood and federally qualified health centers operate under two different sets of regulations and procedures. Health centers can choose which family planning services to offer based on need, but they do need to provide some of those services. As part of its mission statement, Planned Parenthood provides extensive family planning services.

“I think there’s some misnomers that any community health center can pick this up because the Title X grant has some different requirements that federally qualified health centers don’t have to meet,” Adams said. “The concern is, can they operate on two really different sets of rules and regulations.”

Other concerns

If Congress votes to block Planned Parenthood from receiving federal money, some clinics may close, causing increased patient demand at public health centers. The question for patients will be whether those other clinics offer similar family planning services.

Another problem is the time it would take to allow the new funds to reach community health centers.

“Other federally qualified health centers or the county health departments, which in theory could provide the same care that we provide, in theory does have a relationship with the same populations that we do. Even with the chunk of money we get from Title X, it’s not enough for them to sort of revamp their whole delivery system and take on a whole new population,” Nicole Safar, director of government relations for Planned Parenthood of Wisconsin, said.

A federal appeals court on Monday overturned a 2013 Wisconsin law requiring physicians who provide abortion services to have admitting privileges at nearby hospitals. The judges found the law to be unconstitutional because it placed an undue burden on a woman’s right to an abortion.

State Rep. Kylie Oversen, D-N.D., said she does not think the problem is with more money for community health centers, but their accessibility. “They’re not struggling with capacity or resources, but they do not have a great reach to rural communities,” she said.

Cockrum agreed. Community clinics, she said, “don’t put a priority on public transportation. We’re not always able to make sure our locations have public transportation, but that’s a priority for us when we’re locating.”

Another issue to consider, Adams said, is whether patients would be comfortable switching to a different health-care provider.

“To get patients through doors to a provider they may not be familiar with or trust is another piece many don’t think about,” she said. “For some communities, unless they know and trust a provider, it can take 12 to 18 months to build that trust.”

What’s next

The Senate must vote on a spending bill by Dec. 11, when the current spending bill expires. Planned Parenthood funding could come up in several different ways.

One is a House-passed bill that would repeal some aspects of the Affordable Care Act and defund Planned Parenthood.

“It will contain a defund of Planned Parenthood in the Obamacare repeal bill,” Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., said at his weekly press conference Nov. 17. “We’ll be moving to that after Thanksgiving.”

President Barack Obama would veto such a bill.

Many Republicans would prefer that a measure defunding Planned Parenthood instead be part of an overall spending bill. If that passes, Obama could veto it, triggering a government shutdown. Or when legislators return to Capitol Hill next week, they could negotiate a different solution.

“Family Planning Locations” graphic by Jessica Pereda.

Reach reporter Rebecca Anzel at rebecca.anzel@scripps.com or 202-408-1489 and reporter Jessica Pereda at jessica.pereda@scripps.com or 202-408-1493. SHFWire stories are free to any news organization that gives the reporter a byline and credits the SHFWire. Like the Scripps Howard Foundation Wire interns on Facebook and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.

The Scripps Howard Foundation Wire originally published this piece online here.